Mammals and Wildlife

Whales

Blue Whale

Balaenoptera musculus

Blue whales are the largest animals ever to live on our planet. They feed almost exclusively on krill, straining huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates (which hang from the roof of the mouth and work like a sieve). Some of the biggest individuals may eat up to 6 tons of krill in 1 day.

Blue whales are the largest animals ever to live on our planet. They feed almost exclusively on krill, straining huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates (which hang from the roof of the mouth and work like a sieve). Some of the biggest individuals may eat up to 6 tons of krill in 1 day.

Blue whales are found in all oceans except the Arctic Ocean. There are five currently recognized subspecies of blue whales.

The number of blue whales in the world’s oceans is only a small fraction of what it was before modern commercial whaling significantly reduced their numbers during the early 1900s, but populations are increasing globally. Today, blue whales are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Fin Whale

Balaenoptera physalus

The fin whale is the second-largest species of whale. It is found throughout the world’s oceans. It gets its name from an easy-to-spot fin on its back, near its tail.

The fin whale is the second-largest species of whale. It is found throughout the world’s oceans. It gets its name from an easy-to-spot fin on its back, near its tail.

A fin whale has a sleek, streamlined body with a V-shaped head. It has a tall, hooked dorsal fin about two-thirds of the way back on the body that rises at a shallow angle from the back. Fin whales have distinctive coloration: black or dark brownish-gray on the back and sides, white on the underside. Head coloring is asymmetrical—dark on the left side of the lower jaw, white on the right-side lower jaw, and the other way around on the tongue. Many fin whales have several light-gray, V-shaped “chevrons” behind their heads; on many of them, the underside of the tail flukes is white with a gray border. These markings are unique and can be used to identify individual fin whales.

Gray Whale

Eschrichtius robustus

Once common throughout the Northern Hemisphere, gray whales are now only found in the North Pacific Ocean where there are two extant populations: one in the eastern and one in the western North Pacific.

Once common throughout the Northern Hemisphere, gray whales are now only found in the North Pacific Ocean where there are two extant populations: one in the eastern and one in the western North Pacific.

The eastern population was once listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act but successfully recovered and was delisted in 1994. The western population remains very low in number, and is listed as endangered under the ESA and depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Gray whales are known for their curiosity toward boats and are the focus of whale watching and ecotourism along the west coast of North America. Gray whales make one of the longest annual migrations of any mammal, traveling about 10,000 miles round-trip.

These large whales can grow to about 49 feet long and weigh approximately 90,000 pounds. Females are slightly larger than males. Gray whales have a mottled gray body with small eyes located just above the corners of the mouth. Their pectoral flippers are broad, paddle-shaped, and pointed at the tips. Lacking a dorsal fin, they instead have a dorsal hump about two-thirds of the way back on the body, and a series of 6 to 12 small bumps, called “knuckles”, between the dorsal hump and the tail flukes. The tail flukes are nearly 10 feet wide with S-shaped trailing edges and a deep median notch.

Humpback Whale

Megaptera novaeangliae

The humpback whale takes its common name from the distinctive hump on its back. Its long pectoral fins inspired its scientific name, Megaptera, which means “big-winged.” Humpback whales are a favorite of whale watchers―they are often active at the water surface, for example, jumping out of the water and slapping the surface with their pectoral fins or tails.

The humpback whale takes its common name from the distinctive hump on its back. Its long pectoral fins inspired its scientific name, Megaptera, which means “big-winged.” Humpback whales are a favorite of whale watchers―they are often active at the water surface, for example, jumping out of the water and slapping the surface with their pectoral fins or tails.

Humpback whales live in oceans around the world. They travel incredible distances every year and have one of the longest migrations of any mammal on the planet. Some populations swim 5,000 miles from tropical breeding grounds to colder, productive feeding grounds. Humpback whales feed on krill (small shrimp-like crustaceans) and small fishes by straining huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates.

Humpback whales’ bodies are primarily black, but individuals have different amounts of white on their pectoral fins, their bellies, and the undersides of their flukes (tails). Many Southern Hemisphere humpback whales have extensive amounts of white on their flanks and bellies. Northern hemisphere humpback whales tend to have fewer white markings.

Humpback whale flukes can be up to 18 feet wide—they are serrated along the trailing edge, and pointed at the tips. Tail fluke patterns, in combination with varying shapes and sizes of the dorsal fin and/or prominent scars, are unique to each animal. They are distinctive enough to be used as “fingerprints” to identify individuals.

When photographed, scientists can catalog individuals and track them over time, a process called photo-identification.

Killer Whale (Orca)

Orcinus orca

The killer whale, also known as orca, is one of the top marine predators. It is the largest member of the Delphinidae family, or oceanic dolphins. Members of this family include all dolphin species, as well as other larger species such as the long-finned pilot whales and short-finned pilot whales, whose common names also contain “whale” instead of “dolphin.”

The killer whale, also known as orca, is one of the top marine predators. It is the largest member of the Delphinidae family, or oceanic dolphins. Members of this family include all dolphin species, as well as other larger species such as the long-finned pilot whales and short-finned pilot whales, whose common names also contain “whale” instead of “dolphin.”

Found in every ocean in the world, they are the most widely distributed of all cetaceans (whales and dolphins). Scientific studies have revealed many different populations with several distinct ecotypes (or forms) of killer whales worldwide—some of which may be different species or subspecies. They are one of the most recognizable marine mammals, with their distinctive black and white bodies. Globally, killer whales occur in a wide range of habitats, both open seas and coastal waters.Taken as a whole, the species has the most varied diet of all cetaceans, but different populations are usually specialized in their foraging behavior and diet. They often use a coordinated hunting strategy, working as a team like a pack of wolves.

Killer whales are mostly black on top with white undersides and white patches near the eyes. They also have a gray or white saddle patch behind the dorsal fin. These markings vary widely between individuals and populations. Adult males develop disproportionately larger pectoral flippers, dorsal fins, tail flukes, and girths than females.

- https://archive.fisheries.noaa.gov

- They have a scaleless body, which is covered with extremely thick, elastic skin.

- They have a very small mouth with fused teeth similar to a parrot beak.

- Dorsal and Anal fins are very high and used sychronously from side to side and can propel the fish at surprisingly good speed.

- Shortfin mako sharks have pointed snouts and long gill slits.

- They have dark blue-gray backs, light metallic blue sides, and white undersides.

- Their teeth are conical and pointy and protrude forward from the jaw, making them visible even when their mouth is closed.

- They can be easily confused with the longfin mako shark (Isurus paucus).

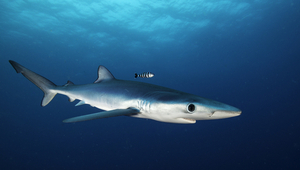

- Long slender body

- Dark blue colour on top, bright blue colour on the sides and white underneath

- Very long pectoral fins

- Nictitating membrane over eye

- Thresher sharks are brown, gray, blue-gray, or blackish on the back and underside of their snout.

- They are lighter on the sides, and fully white below.

- Fins are blackish, and some have white dots on the tips.

- Their tail fin is sickle-shaped, and the upper part is very long, about half the length of the body.

Minke Whale

Balaenoptera acutorostrata

Minke whales are the smallest of the “great whales,” also known as rorquals. They are members of the baleen whale family. With a population status that is considered stable throughout nearly their entire range, minke whales are the most abundant rorqual in the world. Their stability is particularly impressive, compared to other species of large whales.

Minke whales are the smallest of the “great whales,” also known as rorquals. They are members of the baleen whale family. With a population status that is considered stable throughout nearly their entire range, minke whales are the most abundant rorqual in the world. Their stability is particularly impressive, compared to other species of large whales.

The minke whale populations have been reduced in the western North Pacific, potentially due to commercial whaling practices. In the northeastern North Atlantic, the population may have been reduced by as much as half. However, with larger whale species being targeted by commercial whaling more frequently, minke whales may have been able to prosper, thanks to less competition and increased availability of food resources.

Minke whales get their name from Meincke, a novice Norweigian whaling spotter who allegedly mistook a minke whale for a blue whale. Balaenoptera acutorostrata, the scientific name for minke whales, translates to “winged whale” and “sharp snout.”

Although minke whales can weigh up to 20,000 pounds and reach lengths of up to approximately 35 feet, they are still the smallest baleen whales in North American waters. These rorquals are dark in color (black to dark gray or brown) with a relatively small, sleek body and a white underside. They have a fairly tall, sickle-shaped dorsal fin located about two-thirds down their back and a pale chevron on the back of their head, as well as above the flippers. Female minke whales can sometimes be larger than males, and calves are usually a bit darker in color, compared to adults. Rather than teeth, the minke whale has baleen, which are long, flat plates of keratin that hang from the whale’s mouth.

The appearance of a minke whale can vary in body size, patterns, coloration, and baleen. These variations typically depend on geographic location, and can differ from whale to whale. Compared to other minke whales, northern minke whales are smaller in size, and are distinguished by a well-defined white band on the middle of their flippers. They have approximately 50 to 70 abdominal pleats along their throat and 230 to 360 baleen plates on either side of their mouth, which are short and white or cream-colored.

Dwarf minke whales are a subspecies of the northern minke whale that is much smaller in size — typically weighing only up to 14,000 pounds and growing about 26 feet in length. Aside from their size, they can be distinguished by characteristics such as a black border along the baleen plates, a bright white patch on the upper portion of the pectoral fin, and a dark half-collar that wraps around that head all the way to the throat grooves.

Antarctic minke whales have 22 to 38 abdominal pleats along their throats. Their pectoral flippers are generally solid gray with a white leading edge, as opposed to the white band. Additionally, they have 200 to 300 baleen plates on each side of their mouths, which are colored in an asymmetrical fashion — there are more white plates on the right side of the forward part of their mouth than on the left, with the remaining plates being gray in color.

These are other whales that are less common here on the West Coast for us to see:

Seals and Sea Lions

California Sea Lions

Zalophus californianus

California sea lions are “eared seals” native to the West Coast of North America. They live in coastal waters and on beaches, docks, buoys, and jetties. They are easily trained and intelligent and are commonly seen in zoos and aquariums. California sea lions are playful, intelligent, and very vocal (sounding like barking dogs).

California sea lions are “eared seals” native to the West Coast of North America. They live in coastal waters and on beaches, docks, buoys, and jetties. They are easily trained and intelligent and are commonly seen in zoos and aquariums. California sea lions are playful, intelligent, and very vocal (sounding like barking dogs).

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Harbor Seals

Phoca vitulina

Harbor seals are part of the true seal family. All true seals have short forelimbs, or flippers. They also lack external ear flaps and instead have a small hole (opening to the ear canal) on either side of their head.

Harbor seals are part of the true seal family. All true seals have short forelimbs, or flippers. They also lack external ear flaps and instead have a small hole (opening to the ear canal) on either side of their head.

Harbor seals weigh up to 285 pounds and measure up to 6 feet in length. Males are slightly larger than females, and seals in Alaska and the Pacific Ocean are generally larger than those found in the Atlantic Ocean.

Harbor seals have short, dog-like snouts. The color of each seal’s fur varies but there are two basic patterns: light tan, silver, or blue-gray with dark speckling or spots, or a dark background with light rings.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Dolphins

A Dolphin is a small, toothed whale. Like all whales, dolphins are mammals, not fish. Mammals, unlike fish, feed their young with milk that is produced in the mother’s body. Also unlike fish, dolphins have lungs and are warm-blooded-that is, their body temperature always stays about the same, regardless of the temperature of their surroundings. Many scientists believe that dolphins rank among the most intelligent animals, along with chimpanzees and dogs.

Dolphins and other whales make up a group of mammals called cetaceans. Most species of marine dolphins live only in salt water. These animals inhabit nearly all the oceans. Many species remain near land for most of their lives, but some marine dolphins live in the open sea. A different family of cetaceans, called river dolphins, live in fresh or slightly salty water; we don’t have any of these in San Diego.

Marine dolphins are closely related to porpoises, another group of sea mammals. Most zoologists classify marine dolphins and porpoises into one family consisting of about 40 species. The chief differences between dolphins and porpoises occur in the snout and teeth. “True” dolphins have a beaklike snout and cone-shaped teeth. “True” porpoises have a rounded snout and flat or spaded-shaped teeth. However, these characteristics are not present in all species.

Bodies of Dolphins

All dolphins have torpedo-shaped bodies, which enable the animals to move through the water quickly and easily. They have a pair of paddle-shaped forelimbs called flippers, but no hindlimbs. Most species of dolphins also have a dorsal fin on their back. This fin, along with the flippers, helps balance the animal when it swims. Powerful tail fins, called flukes, propel dolphins through the water.

The skin of dolphins is smooth and rubbery. A layer of fat, called blubber, lies beneath the skin. The blubber keeps dolphins warm and acts as a storage place for energy. It is lighter than water, and so it probably also helps dolphins stay afloat.

Like all other mammals, dolphins have lungs. The animals must surface regularly to breathe air and usually do so once or twice a minute. A dolphin breathes through a blowhole, a nostril on top of its head. The dolphin seals its blowhole by means of powerful muscles most of the time while underwater.

Dolphins have a highly developed sense of hearing. They can hear a wide range of low and high-pitched sounds, including many that are beyond human hearing. Dolphins also have good vision, and the entire surface of their bodies has a keen sense of touch. All these senses function well both above and below the surface of the water. Dolphins have no sense of smell and little, if any, sense of taste.

Dolphins have a natural sonar system called echolocation, which helps them locate underwater objects in their path. A dolphin locates such objects by making a series of clicking and whistling sounds. These sounds leave the animal’s body through the melon, an organ on the top of the head. The melon consists of special fatty tissue that directs the sound forward. Echoes are produced when the sounds reflect from an object in front of the dolphin. By listening to the echoes, the animal determines the location of the object.

Most kinds of dolphins have a large number of teeth; some species have more than 200. Dolphins use their teeth only to grasp their prey, which are chiefly fish and cephalopods (octopus/squid). Dolphins swallow their food whole and usually eat the prey headfirst.

Life of Dolphins

Most dolphins mate in spring and early summer. During courtship, the males, called bulls, and the females, called cows, bump heads and also take part in other rituals. The pregnancy period for most species of dolphins lasts from 10-12 months. The females almost always give birth to one baby, called a calf, at a time. One or more female dolphins may help the mother during birth. The calf is born tail first and immediately swims to the surface, sometimes with its mother’s help, for its first breath of air. A newborn dolphin is about a third as long as its mother.

Female dolphins, like all female mammals, have special glands that produce milk. The calf drinks the milk from its mother’s nipples. The females nurse and protect their young for more than a year. Male dolphins take no part in caring for the young.

Most species of dolphins live at least 25 years. Some pilot whales reach 50 years of age. Sharks are the chief natural enemies of dolphins.

Dolphins swim by moving their flukes up and down. This action differs from that of most fish, which propel their tails side to side. Dolphins use their flippers to make sharp turns and sudden stops. Killer whales and some smaller species of dolphins can swim at speeds of up to 25 miles per hour, but only for short periods of time.

Dolphins do not usually dive deeply, though they have the ability to do so. Some dolphins have been trained to dive more than 1,000 feet. When a dolphin dives, its lungs collapse and its heart rate slows. These actions allow the animal’s body to adjust to the increasing pressure as the dolphin dives deeper underwater.

Dolphins and People

The attraction between dolphins and people goes back thousands of years. Ancient Greek artists decorated coins, pottery, and walls with pictures of dolphins, and the animals appear in Greek and Roman mythology. The ancient Greeks considered the common dolphin sacred to the god Apollo. For centuries, sailors have regarded the presence of dolphins near ships as a sign of a smooth voyage.

On the other hand, hunters of several nations kill thousands of dolphins.

Common Dolphins

Delphinus delphis

Common dolphins have several distinct features. For example, a dark band around their eyes extends to the end of their long, narrow beak. Common dolphins also have black backs, white undersides, and prominent gray and yellowish-brown stripes on their sides. These dolphins grow from 6 to8 feet long and weigh up to 165 pounds.

Common dolphins have several distinct features. For example, a dark band around their eyes extends to the end of their long, narrow beak. Common dolphins also have black backs, white undersides, and prominent gray and yellowish-brown stripes on their sides. These dolphins grow from 6 to8 feet long and weigh up to 165 pounds.

Common dolphins live in warm or tropical waters. They often swim in large pods and are frequently seen in the open ocean. Common dolphins sometimes follow vessels for many miles. We see this frequently on the Legacy. As they do so, these playful dolphins may leap out of the water and turn somersaults.

Short-beaked common dolphins are small, measuring under 6 feet long and weighing about 170 pounds. As adults, males are slightly larger than females. They have a rounded forehead (known as a melon), a moderately long rostrum, and 40 to 57 pairs of small sharp teeth in each jaw. Their body is sleek with a relatively tall, triangular dorsal fin in the middle of their back.

Short-beaked common dolphins can be identified by their distinctive color pattern, which is often referred to as an ‘hourglass.’ A dark gray cape extends along the back from the head to just below the dorsal fin where a “V” is visible on either side of the body, creating an hourglass. Forward of the dorsal fin, behind the head, is a yellow/tan panel that contrasts with their dark back, and the side of the body behind the dorsal fin is light gray. A narrow dark stripe extends from the lower jaw to the flipper, and there is a complex facial color pattern that includes a dark stripe from the rostrum, or “beak,” to the flipper. The eye is not typically within the stripe, but the eye stands out due to a patch of dark pigment around the eye.

The color patterns of young and juvenile short-beaked common dolphins are somewhat more muted and pale than older, adult dolphins. Considerable variation in color patterns are evident within populations but more markedly different coloration patterns are evident in some distant geographic areas.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Pacific White Side Dolphins

Lagenorhynchus obliquidens

These dolphins have a robust body, short rostrum (snout), and large dorsal fin compared to their overall body size. Their back, fluke (tail), and lips are black; their sides, dorsal fin, and flippers are gray; and their belly is white. They have a white or light gray stripe along their sides that extends from the eye to the tail, sometimes referred to as “suspenders.” Pacific white-sided dolphins are most likely to be confused with common dolphins and Dall’s porpoises because they have similar large light-colored flank patches.

These dolphins have a robust body, short rostrum (snout), and large dorsal fin compared to their overall body size. Their back, fluke (tail), and lips are black; their sides, dorsal fin, and flippers are gray; and their belly is white. They have a white or light gray stripe along their sides that extends from the eye to the tail, sometimes referred to as “suspenders.” Pacific white-sided dolphins are most likely to be confused with common dolphins and Dall’s porpoises because they have similar large light-colored flank patches.

The average adult Pacific white-sided dolphin weighs about 300 to 400 pounds and is between 5.5 and 8 feet long, with males being generally larger than females.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Bottlenose Dolphins

Tursiops truncatus

Bottlenose dolphins are the best-known species. Their short beaks give these dolphins an expression that looks like a smile. Most of the performing dolphins in amusement parks, aquariums and zoos are Bottlenose dolphins. Members of this species measure up to 15 feet long and can weigh as much as 440 pounds. They are gray, but their backs are darker than their undersides. Bottlenose dolphins show apparent great friendliness toward people and often swim alongside the Legacy.

Bottlenose dolphins are the best-known species. Their short beaks give these dolphins an expression that looks like a smile. Most of the performing dolphins in amusement parks, aquariums and zoos are Bottlenose dolphins. Members of this species measure up to 15 feet long and can weigh as much as 440 pounds. They are gray, but their backs are darker than their undersides. Bottlenose dolphins show apparent great friendliness toward people and often swim alongside the Legacy.

Bottlenose dolphins live in warm or tropical waters. Most of them stay within 100 miles of land. Many live in bays and protected inlets, where the water is relatively shallow. Bottlenose dolphins frequently appear off the coast of Florida and Southern California. They range as far north as Japan and Norway and as far South as Argentina, New Zealand and South Africa.

Common bottlenose dolphins get their name from their short, thick snout (or rostrum). They are generally gray in color. They can range from light gray to almost black on top near their dorsal fin and light gray to almost white on their belly. Bottlenose dolphins living in nearshore coastal waters are often smaller and lighter in color than those living offshore.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Risso’s Dolphin

Grampus griseus

Risso’s dolphins have a robust body with a narrow tailstock. These medium-sized cetaceans can reach lengths of approximately 8.5 to 13 feet and weigh 660 to 1,100 pounds. Males and females are usually about the same size. They have a bulbous head with a vertical crease and an indistinguishable beak. They have a tall, curved, sickle-shaped dorsal fin located mid-way down their back.

Risso’s dolphins have a robust body with a narrow tailstock. These medium-sized cetaceans can reach lengths of approximately 8.5 to 13 feet and weigh 660 to 1,100 pounds. Males and females are usually about the same size. They have a bulbous head with a vertical crease and an indistinguishable beak. They have a tall, curved, sickle-shaped dorsal fin located mid-way down their back.

Calves have a dark cape and saddle, with little or no scarring on their body. As Risso’s dolphins age, their coloration lightens from black, dark gray, or brown to pale gray or almost white. Adult bodies are usually heavily scarred, with scratches from teeth raking between dolphins, as well as circular markings from prey (e.g., squid), cookie-cutter sharks, and lampreys. Mature adults swimming just under the water’s surface usually appear white.

Risso’s dolphins have two to seven pairs of peg-like teeth in the front of their lower jaw to capture prey and usually none in their upper jaw. This low number of teeth is unusual when compared with other cetaceans.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Birdlife

Heerman’s Gull

Larus heermanni

Medium-sized gull, about the size of a crow. It has long wings and a red bill that is relatively long, angled, and black-tipped.

Medium-sized gull, about the size of a crow. It has long wings and a red bill that is relatively long, angled, and black-tipped.

Western Gull

Larus occidentalis

Large, white-headed gull with a dark gray back, yellow bill, and pink legs. Breeding adults have an orange ring around the eye and a red spot on the lower part of their bill.

Large, white-headed gull with a dark gray back, yellow bill, and pink legs. Breeding adults have an orange ring around the eye and a red spot on the lower part of their bill.

California Gull

Larus californicus

This gull is medium-sized, with yellow legs, a dark eye, and a red spot on their lower bill. They are white with a medium gray back. Non-breeding adults have a heavily streaked head.

This gull is medium-sized, with yellow legs, a dark eye, and a red spot on their lower bill. They are white with a medium gray back. Non-breeding adults have a heavily streaked head.

Royal Tern

Thalasseus maximus

These are large terns, with short black legs, a forked tail, and a long, daggerlike orange beak. Breeding adults have a black crown, while non-breeding adults often have a shaggy band on the back of their heads.

These are large terns, with short black legs, a forked tail, and a long, daggerlike orange beak. Breeding adults have a black crown, while non-breeding adults often have a shaggy band on the back of their heads.

Elegant Tern

Thalasseus elegans

A medium-sized tern with a long, thin, drooping orange bill and pointed wings. They have a forked tail, and may have a shaggy black crest on the back of the head.

A medium-sized tern with a long, thin, drooping orange bill and pointed wings. They have a forked tail, and may have a shaggy black crest on the back of the head.

Least Tern

Sternula antillarum

The smallest North American tern, between the size of a robin and a crow. It is slender with narrow pointed wings and a white forehead, as well as a yellow bill and legs.

The smallest North American tern, between the size of a robin and a crow. It is slender with narrow pointed wings and a white forehead, as well as a yellow bill and legs.

Pacific or Common Loon

Gavia pacifica

Both types of loons have a checkered back, but a common loon has a thicker bill, darker head, and a striped collar.

Both types of loons have a checkered back, but a common loon has a thicker bill, darker head, and a striped collar.

Pink Footed Shearwater

Ardenna creatopus

This bird’s pink feet may be difficult to see, but it has a pink bill with a dark tip, white belly, and smudgy brown neck and underwings.

This bird’s pink feet may be difficult to see, but it has a pink bill with a dark tip, white belly, and smudgy brown neck and underwings.

Black Vented Shearwater

Puffinus opisthomelas

This shearwater is small with brown and white coloring — smudgy coloring on the head and neck. They have a long bill and dark coloring under the tail.

This shearwater is small with brown and white coloring — smudgy coloring on the head and neck. They have a long bill and dark coloring under the tail.

Brandt’s Cormorant

Phalacrocorax penicillatus

Larger bird with an oval-shaped body, long neck, long hooked bill, short legs, and large webbed feet. Breeding adults are black with a purple sheen on the head and a blue skin patch on their chin.

Larger bird with an oval-shaped body, long neck, long hooked bill, short legs, and large webbed feet. Breeding adults are black with a purple sheen on the head and a blue skin patch on their chin.

Double Crested Cormorant

Phalacrocorax auritus

These large birds have a long neck, small head, and long hooked bills. Adults are brownish-black with a small patch of orange-yellow skin on the face.

These large birds have a long neck, small head, and long hooked bills. Adults are brownish-black with a small patch of orange-yellow skin on the face.

Brown Pelican

Pelecanus occidentalis

These are huge birds with a thin neck and extremely long bill with a stretchy throat pouch for catching fish. Adults are gray-brown with a yellow patch on the head.

These are huge birds with a thin neck and extremely long bill with a stretchy throat pouch for catching fish. Adults are gray-brown with a yellow patch on the head.

Cassin’s Auklet

Ptychoramphus aleuticu

Small, stocky seabird with a round head and short neck. It is dark gray in color with white crescents above and below the eyes. Its bill is short, thick, and upturned.

Sharks and Fish

Giant Sunfish (Mola Mola)

https://www.fishbase.de/summary/1732

Pacific Shortfin Mako Shark

Isurus oxyrinchus

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov

Blue Shark

Prionace glauca

Pacific Common Thresher Shark

Alopias vulpinus